- Aromatherapy for Weight Loss

- Fighting Obesity: The Role of Behavior, Biology and Bad Choices

- Fighting Obesity: Psyching Yourself to Act

- Fighting Obesity: Why Moving More is Crucial

- Fighting Obesity: Eating to Be Healthy and Lean

- Healthy Eating Tips

- Nutrition & diet information

- Diet Myths

Part 1 in a four-part series on obesity and weight loss

If you’re carrying around extra flab, the good news is that in times of famine you would have had a good chance of survival. That’s because fat is energy and the body conveniently packs it away in cells called adipocytes so that a ready supply is always available. Of course, today, not only is there little chance of famine in the Western world, but food is everywhere. And since the body is hardwired to be thrifty, it keeps on doing what it does best—storing all the extra calories that you consume.

The fat has nowhere to go but around your waist, on your hips, beneath your chin, on your arms—wherever you have fat depots. Some people have many fat cells that are moderately packed with fat. Others have fewer fat cells that are stuffed to the brim. And, if the body runs out of closet space, it can create new fat cells to store the extra. Having too much fat, especially around the belly, is a liability in today’s sedentary world and is associated with a variety of health risks.

Are You Fat ?

When a person weighs more than what is considered average for their height and age, they are overweight. This is typically measured on a scale. But scale weight can be misleading because it does not assess body fat or how tall you are—both of which can affect whether your weight is healthy or not. When a person has a significant amount of excess body fat, they are considered obese. This is best measured in a lab (the body fat scales you can buy in the store are not highly accurate). For research purposes, a simple equation that factors in both body weight and height is often used. This is the body mass index (BMI). People with a BMI of 25 to 29.9 are considered overweight. Those with a BMI of 30 and above are considered obese. A woman who is 5-foot-5, for example, would be overweight if she weighs more than 150 pounds. She would be obese if she weighed more than 180 pounds. A man who is 5-foot-11 is considered overweight if he weighs over 179 pounds and obese if over 215 pounds. (The 25- to 30-pound range for each BMI category was determined because fat-related health risks were seen to increase at those increments.) You can calculate your BMI here. BMIs aren’t a perfect measure of fatness, though. Fit people tend to have more muscle mass and they may weigh more even though they are quite lean. For example, a highly athletic man may seem overweight according to a BMI scale, when in fact he is a healthy weight.

No matter what a person’s BMI is, fat people tend to fit into one of five categories:

The Staying-Fat are those who are overweight and know it, yet they either don’t care or they have given up trying to fight it.

The Yo-Yo’ers are those people are overweight and who try and do lose weight, usually through dieting. But then they gain it back again—often accruing more fat with each cycle of weight loss.

The Finally-Not-Fat are those who diligently work at controlling their weight. Once they lose it, they manage to keep most of it off. These are known as successful losers or weight-loss maintainers. But even though they now may be thin—or at least thinner—they may always have a fat person’s physiology. So, their responses to diet and exercise may be different than those of an always-lean person of the same height and weight.

The Blindly Fat are those who are overweight or even obese, but don’t think that it’s a problem and so aren’t currently trying to lose weight. These people either don’t think or don’t admit to carrying extra fat. One recent study found that adult participants who were clinically obese tended to have a rosy perception of their weight status: 85 percent did not consider themselves to be obese.

The Feeling Fat are those who are not overweight and may even be lean. Yet they see themselves as fat—they want to lose an extra five or 10 pounds or they have bulges in certain places that they’d like to whittle down. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that nearly a quarter of women and 6 percent of men of normal weight are trying to shed pounds.

It’s a good idea to recognize which category describes you, because understanding your perceptions and behaviors can help you figure out the most effective way to get your weight under control.

What Makes You Fat ?

Although skinny people sometimes attribute fatness to laziness, it’s not so simple. There are plenty of thin, lazy people who eat poorly and get no exercise. The reason that some people become fat is a complex interaction between who they are and how they live.

Your genes absolutely play a role. If you have one parent who is fat, your risk is increased. If both parents are fat, your risk is increased even more. Researchers estimate that as much of 60 percent of obesity risk is genetic. So far over 600 genes and chromosomal regions have been linked with human obesity, but more are being decoded all the time. Still, we do know that for most people, there are many factors involved and it’s not genes alone that determine obesity. Although you may share DNA with your parents, you may also share lifestyle behaviors that encourage you to be—and keep you—fat.

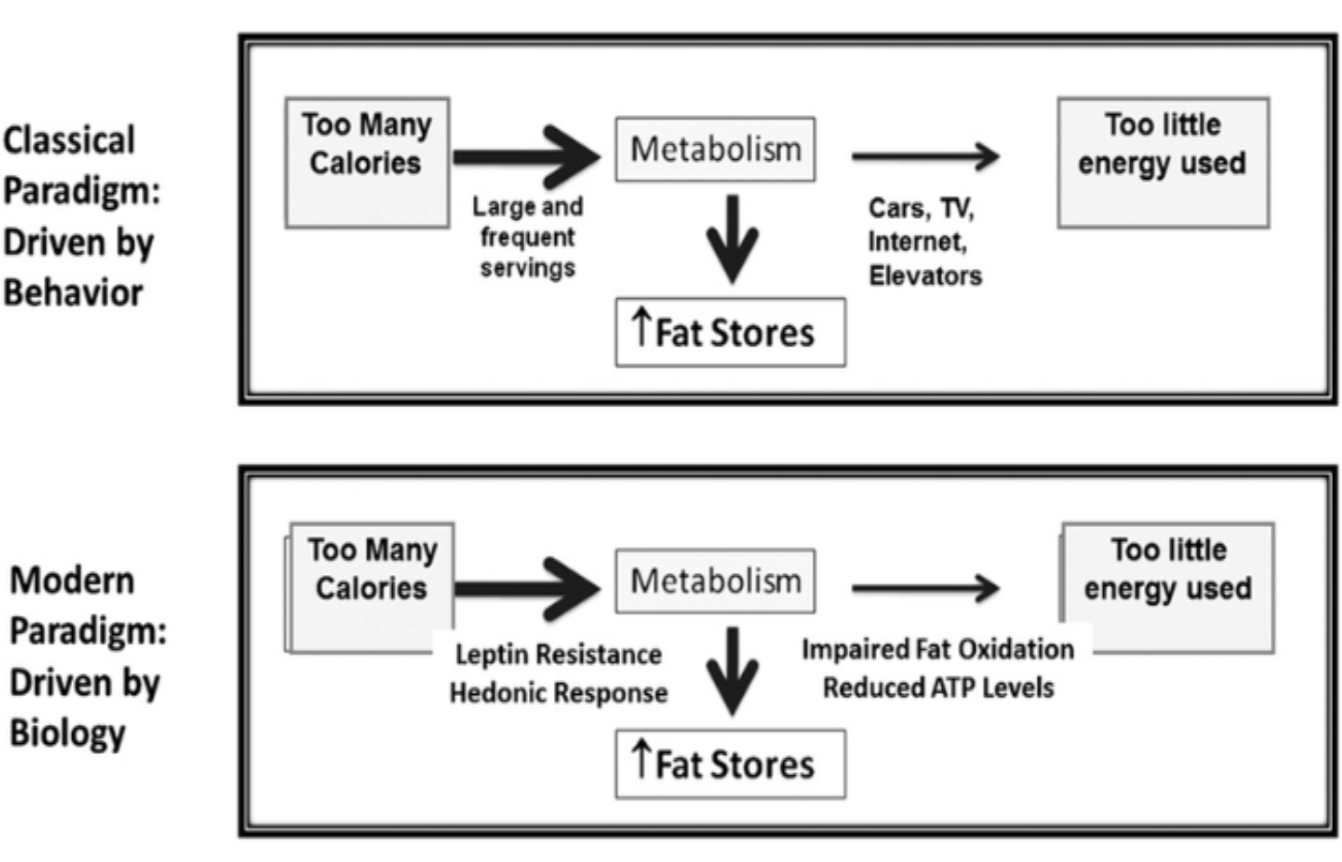

One just needs to look at what’s happening in the U.S. for proof. The human genome has not changed in the past two decades, but obesity levels have dramatically increased in this country during that time. What has changed is the way that people live: The environment is obesigenic, or, rather, it helps to make you fat. All the junky fast food, calorie-filled drinks, huge portions and couch-potato, car-driving, desk-working living have triggered those who are prone to it to become obese. In another environment where famine was a reality, these people might have lived the longest. But in this modern setting, they may end up with heart disease, diabetes and other conditions that result from carrying too much fat. If you are fat, you may not have control over whether you are susceptible to packing on extra weight, but you do have control over how much weight you gain.

What Keeps You Fat ?

In this obesigenic environment, everyone is prone to weight gain, even lean people. They may not become obese, but they can easily gain one or two pounds a year so that from ages 20 to 50 they may have gradually gained 30 or more pounds. The first study ever to assess the long-term risk of weight gain was done on 4,000 white adults who were part of the well-known Framingham Study. Over a 30-year period, researchers found that 90 percent of the men and 70 percent of the women became overweight and 33 percent became obese. A large majority went from being overweight to obese in just a four-year period. That quick transition suggests that lifestyle behaviors—what you eat, how you active you are—are behind the rapid rise. The good news is that you can live a leaner lifestyle. It’s not always easy, but it can be done.

It is easier to gain weight than to lose it, and it is easier to lose it than to keep it off. Fat-prone folks may have an even easier time gaining and an even harder time losing—and maintaining that loss—than lean people. Individual biological differences are the culprit. For example, hormones, neurotransmitters and other physiological factors may be secreted in different amounts or at different times than in a lean person—and this can affect all aspects of eating and activity. For example, you might have a faster release of the hormone that makes you hungry. Or you may have a higher threshold of food intake before factors that trigger satiety kick in, which means you may feel less full from the same-sized meal as someone else. Or, pictures of food in a TV commercial might spark a craving that prompts you to seek out something to eat, whereas a lean person might not have that same mental response.

How active you tend to be may also be dictated by biological factors. You may be less prone to fidgeting and more inclined to sit throughout the day. You may experience fewer sensations of pleasure and enjoyment from, say, riding a bike than a regular exerciser would. (And that can affect how easy it is for you to stick to a fitness regimen.) If you do diet and lose weight, you may trigger a biochemical surge that spikes your appetite more than normal, which means you’ll need to exert tough love on yourself to fight the urge to gorge. You might not even have to eat more for your body to be predisposed to storing more fat than another person.

These sorts of internal processes mean that, as a fat person, you may not be on level ground with an always-lean person. And you may have to work harder to keep your weight under control. But you can do it, and you can make it easier by working smarter. The first step is understanding your status, your limitations and the obstacles you may face.

How Weight Loss Works ?

Weight gain comes from eating more energy than you expend. It’s as simple as that. In theory, eating 3,500 more calories than your body burns up will lead to a gain of one pound of fat.

But in reality, a calorie may not be the same for every body. Genetic and biological factors may influence the amount of weight lost from dieting as well as weight gained from overeating. In one study, twins were overfed 1,000 calories per day for almost three months. Researchers expected that the weight gain across all the participants would be roughly the same. And it was very similar between each pair of twins, as was the amount of abdominal fat they gained and where the fat was distributed. But across pairs the results were strikingly different: From the same amount of overeating, the weight gain ranged from 10 pounds to 30 pounds.

Some studies have showed that dieting doesn’t result in much weight loss for some people. And for some severely obese people, a lifetime of endless diets may trigger fat-preservation mechanisms to kick in harder, making these people gain more and more as they continue to fight to lose it. If you’ve followed a yo-yo pattern, then going on a drastic diet may not be the smartest approach for you long term.

Going for the Quick Fix

So, if diets don’t always work, wouldn’t a pharmaceutical option be foolproof? Many people are tempted by the lure of popping a pill and watching the weight melt off. Unfortunately, it isn’t that easy. Of the many diet drugs that have been developed in the past 50 years, only two are currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for long-term use. That’s because many weight-loss drugs that have been used over the years have been found to be ineffective or have serious side effects. Even those that are currently on the market may not be as good as they sound. For example, sibutramine (Meridia) does suppress your appetite, but it can raise your blood pressure. And orlistat (Xenical) blocks the absorption of some of the fat that you eat, but you can also get a side effect called “dumping” where you have, um, uncontrolled bowel movements.

What most people don’t realize is that even the best diet drugs are not really that good. A drug is considered to be effective if you lose 5 percent of your body weight in six months. So if you weigh 250 pounds and lose 15 in six months, or about two pounds per month, the drug “works.” Weight loss may be quicker in the first few months from a drug, but like other approaches, the weight loss plateaus and long term, after two or even three years on a drug, the results are not much better than if someone had stuck to healthy eating and become more active. The clincher, to help the drugs work you’re expected to eat better and exercise. So, why pop a pill and risk unpleasant side effects? From my perspective, the result is no better and potentially worse.

Herbal supplements are even riskier. They are completely unregulated and taking them is like volunteering to play guinea pig. Infomercials sound believable. But notice that all supplements advocate improving your eating and exercise habits along with taking the pill. So if you see results, is it from the magic ingredient or the fact that you improved your lifestyle?

The Weight-Loss Secret

The bottom line to slimming down is to improve the way you live. You may have to fight hard and relearn old habits to protect yourself in this fat-promoting world we live in. But you can do it. And I will help you. In the next installment of this four-part series, I will explain how to psych yourself up to win the battle of the bulge.